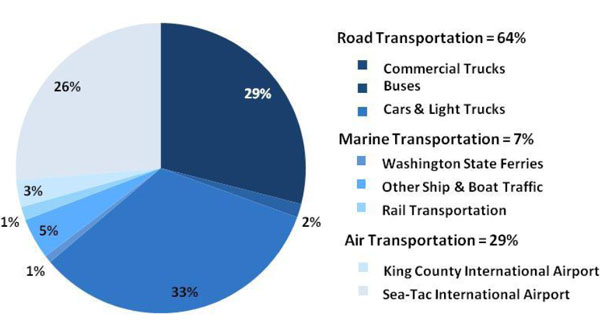

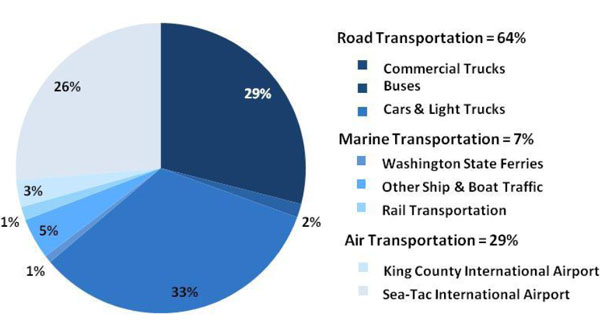

[ Seattle’s 2008 GHG emissions from the transportation sector, which accounts for 62 percent of total emissions ]

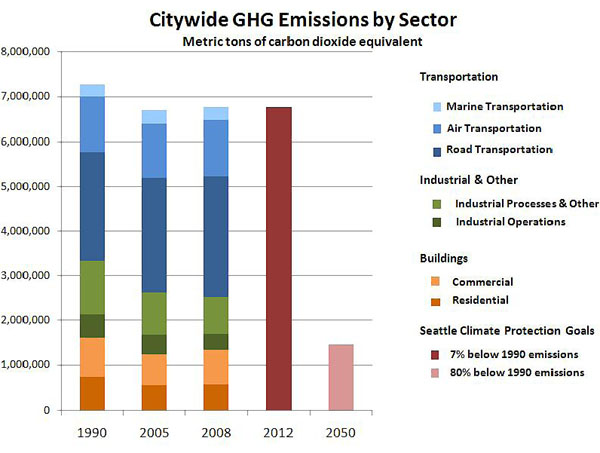

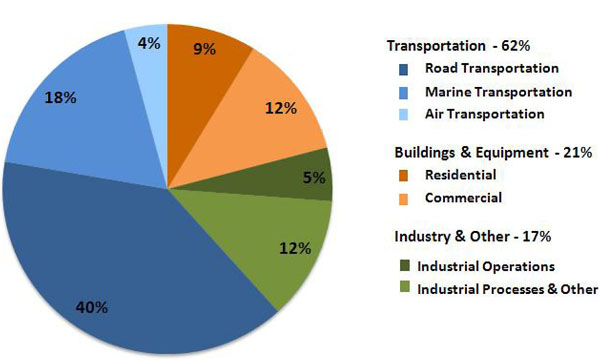

Transportation is not only the single largest source of Seattle’s greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions—accounting for 62 percent—but it is also the only sector from which emissions are still escalating: Seattle’s GHG inventory shows a seven percent increase in emissions from the transportation sector between 1990 and 2008.

There are two ways to reduce transportation emissions: travel less, or increase vehicle efficiency.

First, a word about air transportation: wow. It’s a remarkably large chunk of the transportation footprint considering how small a part of our typical daily lives air travel is compared to driving. Airplanes have passenger-mile efficiencies in the same range as cars—it’s the long travel distances that rack up the GHG emissions. Barring an unexpected breakthrough, it is unlikely that airplanes will ever become significantly more efficient. (Translation: airline stocks are not a wise long-term investment.)

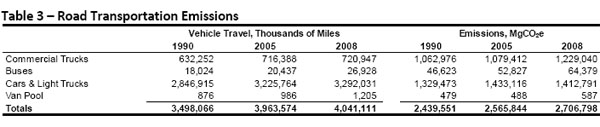

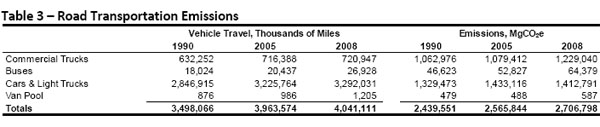

Road travel constitutes nearly two thirds of Seattle’s transportation-based carbon footprint, and it also accounts for most of the increase in emissions since 1990. Crunching the road vehicle miles traveled (VMT) data shown in Table 3 below reveals that per capita VMT in Seattle were nearly identical in 1990 and 2008 (with a slight bump in 2005). In other words, VMT have risen at the same rate as population growth. From 1990 to 2008, passenger vehicle fleet efficiency increased by about nine percent, but that was not enough to offset the increase in emissions due to more driving.

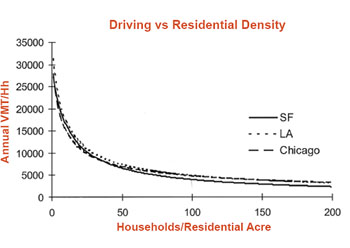

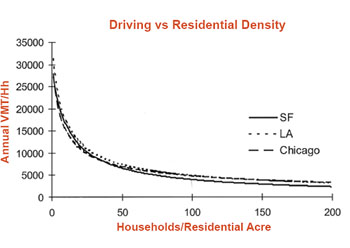

The most promising strategy for reducing travel in personal vehicles is to create compact, walkable neighborhoods served with high-quality transit. This topic has been covered many times on this blog, and the case is made at length in Transit-Oriented Communities: A Blueprint for Washington State, the new report by Futurewise, GGLO, and Transportation Choices Coalition. The graph on the left is a concise summary the story:Â population density is a proxy for the important physical ingredients of transit-oriented communities, and as density goes up, VMT go down.

But some contend that restructuring our built environment is too expensive and will take too long to be an effective response to climate change, and therefore that our focus should be on increasing vehicle efficiency. And the type of vehicle most often touted is the electric car.

Like most urbanists, my feelings about cars were well captured by Lewis Mumford when he wrote, “Forget the damned motorcar and build the cities for lovers and friends.” But has that bias resulted in unfair dismissal of solutions that don’t involve getting rid of cars? Given the dire threat of the climate change, we can’t afford to be hamstrung by such biases.

So the first question to answer is: How much more electricity would be needed if Seattle’s entire fleet was converted to electric vehicles?

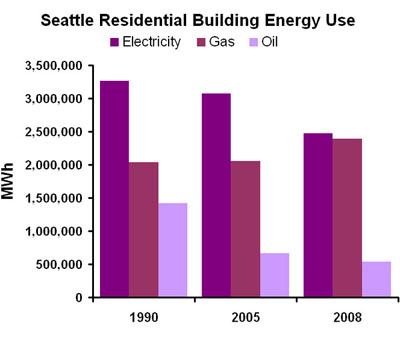

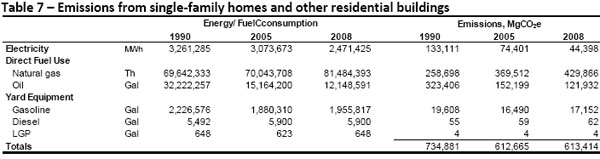

The Nissan Leaf can travel about four miles on one kWh of electrical energy. But since many people need larger cars and light trucks let’s assume an average of 3 miles per kWh for the fleet. The 3,292,031,000 miles traveled by cars and light trucks in Seattle in 2008 would consume about 1,100,000 MWh. That represents a 14 percent increase over Seattle’s total 2008 electricity consumption of about 8,000,000 MWh (data from this report). An all electric fleet of commercial trucks—which are about one fourth as efficient as cars and light trucks—would require another 12 percent.

Thus, the total conversion would add about one quarter to Seattle’s current electrical demand. First reaction: that’s a lot less than I would have guessed given all the kinetic energy involved—we’re not talking about needing to double or triple electricity production or anything totally unfeasible like that.

And what would be the impact on GHG emissions? Because our regional carbon-free hydropower capacity is tapped out, new electrical demand is typically treated as “marginal,” with an emissions factor that assumes electricity is generated from fossil fuels. As discussed in this post, a 3 mile/kWh electric car using marginal electricity with an emissions factor of 600 grams CO2 per kWh, would emit 200 grams of CO2 per mile. Applying those assumptions, the full electric conversion would cut Seattle’s road transportation emissions about in half, which would reduce the City’s total carbon footprint by about one fifth.

That’s a big reduction, but unfortunately still not enough. Though there are two factors that could boost the upside of electric vehicles:

- Our electricity will become less carbon-intensive over time as renewables come on line, resulting in a corresponding drop in GHG emissions associated with electric vehicles.

- Electric cars can charge during off-peaks hours (at night) to take advantage of underutilized electrical generation capacity. And they also could be used as networked storage devices to feed power back to the grid when advantageous.

Of course, there are also many downsides left out of the above analysis:

- There are significant GHG emissions resulting from car use in addition to those associated with simply propelling the car. For example, Toyota estimates that manufacture accounts for 30 percent of a Prius’ lifetime GHG emissions. In addition, the infrastructure required for cars is a source of GHG emissions—one study estimates that roadway construction and maintenance adds another 26 percent to the GHG emissions associated with operating a conventional car.

- Rising fossil fuel costs and carbon pricing will inevitably result in rising demands on carbon-free electricity from all sectors, and electric vehicles may end up competing for energy needed to supply the basics, such as heating homes.

- The Puget Sound region is projected to grow by 1.6 million people by 2040, an increase of more than 40 percent. If we do nothing other than convert our fleet, we can expect VMT to rise proportionally. And in this scenario, we’d have to choose between a massive amount of road building or total gridlock. Note that this this scenario would also mean a forty-plus percent increase in electricity consumed by electric vehicles.

- Electric cars are expensive (it’s all about the batteries). A new $30k electric car for every Seattle household would cost about $9 billion—more than twice the City’s total annual budget of $3.9 billion.

- And lastly, electric cars, like conventional cars, inherently cause a host of negatives, including accidents, high cost of ownership, sedentary lifestyles, social isolation, land consumption, impervious pavement, and the proliferation of terrible urban design.

So then, do we have a verdict on electric cars? First of all, like most ideas applied to the real world, they are not a silver bullet solution. In the short term, it makes sense to get a lot more electric vehicles out on the road as soon as possible, simply because they are much more energy efficient than conventional motor vehicles.Â

In the long term however, it is delusional to think that we can go on with car-centric business as usual if we simply switch to electric vehicles. Indeed, our future prosperity will be determined to a large degree by how successfully we reduce reliance on cars. And that means reshaping our urban areas such that (1) people can meet many of their daily needs with short trips that can be made on foot or bike, and (2) convenient public transit is available for longer trips. (Hint: some folks like to call such places transit-oriented communities.)

The concept could also be criticized for the same reason some object to

The concept could also be criticized for the same reason some object to